The tragedy of Bihar — the devastation wrought because the mighty river Kosi changed course after it breached its embankment in Nepal on August 18 — has slipped off the pages of newspapers and TV screens. The calamity has also been virtually ignored by most international humanitarian aid agencies, and even national relief organisations. The people affected are among the most impoverished in this land, and floods seem to be part of the periodic tribulations that these hapless people stoically cope with, along with caste violence, deaths by starvation and militant violence. Surely this cannot continue to make news!

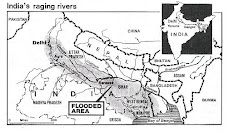

But it would be a grave mistake to regard the destruction by the Kosi river in Bihar as ‘just’ another flood. One of the major tributaries of the Ganga, Kosi is often called the Sorrow of Bihar because of frequent floods and changes in its course. However, what transpired since the embankment collapsed was no ordinary flood. The river impetuously traced a new course, across fields and dense settlements for 150 kilometres, often 15 to 20 kilometres wide. Its untamed waters swept away more than 300,000 houses in 980 villages in the districts of Supaul, Madhepura, Saharsa, Araria and Purnea. It destroyed standing crops of paddy, wheat and vegetables in 110,000 hectares of fertile land. An estimated 3.2 million people lost their homes and livelihood, many times more than in any natural disaster in the country in recent history.

The loss of life has been fortunately small for a disaster of this scale. The government estimates are that 194 people died in the floods, although the figures are hotly contested. But even if the numbers of the dead swell manifold with evidence of missing and drowned people burgeoning over time, it will still be far below the levels of other national natural disasters of the past decade, such as the Orissa super-cyclone of 1999, the Gujarat earthquake of 2001 and the tsunami of 2004, in each of which deaths mounted to tens of thousands of people. But the devastation of homes and livelihood by the wayward river far surpasses the worst of these other disasters.

These are people who had never faced floods in their lifetime because there was no river near their homes to flood its banks. As they incredulously saw with terror the raging waters of the unfamiliar river enter their villages and fields, many declared that this was no flood; they were witnessing pralay or the destruction of the world predicted in the scriptures. In regions with no history of floods, there were no country boats and motor boats for rescue locally available. These had to be requisitioned from other districts, and military, paramilitary and the civil authorities launched one of the largest evacuation operations ever, rescuing hundreds of thousands of people who had taken shelter on embankments, canal walls and the roofs of homes that were still standing.

More than 400,000 women, men and children were housed in relief camps in tents and school and college buildings, whereas others took refuge with relatives and some even left the state. Given the enormous scale of devastation, and relatively very small assistance from international and national humanitarian agencies, the state administration has managed to house large dispossessed populations in orderly camps, with arrangements for food, milk and schooling for the children. Winter will come with fresh challenges for camp residents.

However, as the flood waters have begun to recede, we found that anxious villagers are gradually leaving the camps for their villages, to assess their losses, protect what may be left of their homes and possessions, and pick up the string of their lives. Apart from almost an unprecedented scale of devastation and severe constraints of resources and the impoverishment of the affected people, the greatest impediment is the uncertainty over the future course that the capricious river may choose to take in the years to come. It is being debated among experts whether neglect and corruption in the maintenance of the embankment caused the destructive breach, or whether the design of the embankment was itself intrinsically defective and this was a disaster waiting to happen.

Villagers seek one guarantee from the authorities before they rebuild their homes and try to reclaim their lands and livelihood, and that is that the waters of the river Kosi will not return to their villages in the coming years. But officials off the record affirm that they are unable to provide any such assurance.

The challenges of reconstruction are aggravated further by the fact that the people affected include some of the most chronically indigent in the country, and one of the most unequal and divided societies. Caste and patriarchy made themselves felt even in the orderly government relief camps, where people of disadvantaged castes, single women and old people were denied scarce relief assistance. The majority are landless or unrecorded tenants, and with the landlords’ fields silted over, there is little prospect of work and food unless the government gears itself for massive wage employment public works.

Farms in Punjab may be their only hope for oppressed survival, but they fear that if they leave Bihar, they may miss out on the little relief the government may offer. Even a few thousand rupees are a small fortune for people who survive on nothing. There is a grave danger of the trafficking of children in these areas because of extreme poverty and family distress, or their dropping out of school into child labour. In the face of a human tragedy of this scale, it would be unconscionable for the country to simply look the other way.

Harsh Mander

October 27, 2008 , Hindustan Times

Historically, floods and their control have never been a big issue in the Ganga-Brahmaputra basin, as it is today. Floods became a major issue after the British occupied India. When they examined the Ganga basin, they believed that if it could be made “flood-free”, they could levy a tax in return for such protection.

Monday 27 October 2008

Saturday 18 October 2008

Kosi (Mithila) Crisis: "Kusaha Breach and Thereafter"

At a talk & a day long Panel Discussion in Patna on "Kusaha Breach and Thereafter", heated exchanges between pro-"kosi high dam" engineers and proponents of "living with floods" ended with an apparent conclusion that high dams & embankments are less of an engineering interventions and more of a political intervention. On 17 October, on the eve of two months of the Kosi breach, the talk was delivered by Dr Dinesh Kumar Mishra, a well known voice of sanity with regard to Kosi crisis.

Failure of dams as flood control structures has been demonstrated in Orissa, Gujarat, Maharasthra and Jharkhand.

Disaster management and relief centric narrative that has become the dominant factor came in for severe criticism.

A white paper was demanded, while sharing the Hindi version of the Fact Finding Report on Kosi “Kosi “Pralay”: Bhayaavah Aapada Abhi Baaki Hai” sought accountability of Kosi High Level Committee (KHLC) and provide a remedy for the drainage crisis in North Bihar as was promised by the UPA government's Common Minimum Programme. All the activities of KHLC should be put in suspension till the time their liability is fixed and Justice Rajesh Balia Judicial Commission of inquiry set up on September 9, 2008 is completed. The commission’s recommendations must not meet the fate of several dozens of committees and it must recommend criminal charges against acts of omission and commission.

It is noteworthy that Union Water Resources Department Secretary, in a letter to the Bihar Irrigation Secretary on September 24, 2008 has questioned the locus standi of the judicial commission. The letter read: “The Kosi agreement is a bilateral agreement between two sovereign states, India and Nepal, and Bihar is not a party to either 1954 or the 1966 agreement.”

Water and Power Consultation Services (WAPCOS), a central government’s public sector undertaking has provided technical inputs to the Bihar government on possible ways to plug the breach at Kusaha in Nepal.

Participants included victims of embankments who expressed their anguish at the Delhi, Kathmandu and Patna centric deliberations and decision making. They called for a movement against Kosi High Dam, embankments and changing the current course of Kosi.

Amid news reports that Kosi's course will be restored by December 15 and the breach would be plugged by March 31, 2009 citing Kosi Breach Closure Advisory Technical Committee chairman Nilendu Sanyal and Ganga Flood Control Commission chairman R C Jha on 14 October, 2008 to finalise modalities on plugging the breach, some participants were opposed to the repair of the breach in Kusaha. Government must hear the views of these people before undertaking repair works.

Meanwhile, central government has sanctioned Rs 40 crore for the project and Bihar Cabinet has sanctioned Rs 197 crore. Bihar Water Resources Minister Bijendra Yadav has said tenders for the breach closure have been invited and bidding will take place after October 21.

Kosi is an international river and all interventions must show utmost sensitivity that does not bring a bad name to our country. The onus is the central government to avoid a situation which makes our country a laughing stock for mismanagement of rivers.

It emerged from the discussions that a list of "what not to do in Kosi basin" must be prepared before relying on the suggestions of retired and tired officials like Nilendu Sanyal and his ilk. Post-retirement enlightenment of engineers has more to do with their own rehabilitation less to do with kosi victims welfare.

People of Kosi basin are victims of development and the arrogance of governmental knowledge that are used to scare common people into silence and submission by their declarations such as "I Know the facts".

From K L Rao, Kanwar Sen, K N Lal to Nilendu Sanyal all of them gave flood control solutions...people in Kosi basin are victims of their solution.

Dr Mishra explained why Kosi has been flowing at a level higher than its adjoining mainland. The reduced cross-section of the river due to embankments was expected to facilitate the dredging of its bed. Instead, the Kosi offloaded silt into the river and raised the level of its bed. That the Kosi is among one of the highest silt-laden rivers in the country makes matters worse. Had the river been free to meander, it would have deposited fertile silt, collected from the slopes of Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga, across the plains of north Bihar. But that was not to be, as most of the silt carried over the years lies trapped between river banks, reducing the stream flow on the one hand and making the embankments vulnerable to breach on the other.

He also revisited historical records and official documents arguing that floods caused by this river are not man-made, they are devil-made. Devils being the nexus between politician-engineer-contractors that feeds on the status quo.

Participants included Himanshu Thakkar, Sudhirendar Sharma, Gopal Krishna, Arvind Chaudhary, Kuber Nath Lal, K P Kesari, R K Singh, S K Sinha, Ram Chandra Khan, Shaibal Gupta, PP Ghosh, Rakesh Bhatt, Vijayji, Shivanand Bhai, C P Sinha, C Uday Bhaskar, V N Sharma, RK Sinha, A K Verma, N Sharma, B Singh, Chandrashekhar, T Prasad, Kavindra Pandey, Prem Kumar Verma, Raj Ballabh and several others.

Kosi is synonymous with the history, culture of not only Mithila but whole of the Indian sub-continent. One cannot think of the Indian sub-continent without thinking about Ramayana (Sita) and Mahabharata (Karna). Ramayana and Mahabharata cannot be even imagined in the absence of Mithila. The structural solutions have already distorted the landscape of the Kosi-Mithila region, Kosi High Dam would turn out to be a monument of foolishness for generations to come. Like the villains of embankment proposal, all the kosi high dam proponents must be identified and dealt with by something like a Kosi Sansad.

The proposal to raise a 269-meter-high dam in Sunakhambi Khola on the Sapta Kosi river, 5 km north of Barahachhetra temple in Sunsari district appeared to be an unsound proposition of people who are caught in a time warp. Proposed "Sapta Kosi Multi Purpose Project" claims to irrigate 68,450 hectares in Nepal and provide remedy for drought-prone areas measuring 1,520,000 hectares in India. It is claimed that alongwith irrigation and flood control, about 3,500 MW of electrical power would also be generated from water stored in the 269-meter-high reservoir.

According to a preliminary impact study, the proposed high dam will displace 75,000 people from about 79 Village Development Committees (VDCs) in nine districts of Nepal alone. About 111 settlements in the 79 VDCs, sprawling over the banks of the Sun Kosi, Tamor, and Arun rivers, will be totally submerged, while 47 settlements will face partial submergence, and 138 will become fractionally submerged.

Opinions available in public domain say, "If the dam is going to cause such upheaval, can the crops produced from the 68,450 hectares of irrigated land in Nepal compensate for this huge loss?" argued the bimonthly magazine, Pro Public/Good Governance, in its report. Estimated losses in the North Bihar are yet to be ascertained.

Elsewhere on the web Vinay Jha, Editor, Mithila Times argues that the kosi High Dam is actually a population-control plan by the government; a dam break in an earthquake prone zone will eradicate poverty in a vast region by eradicating the poor. Narural flow of rivers and natural habitats must not be tampered with, which we must maintain if we want life to exist on Earth. Instead of a gigantic dam, what we need is a gigantic network of very small scale water management schemes, including a vast network of small dams in Himalayas. But Indian officials can never think or manage such schemes.

Earlier, the meeting of the Indo-Nepal Joint Committee on Water Resources in Kathmandu on October 2, 2008 agreed to expedite work on preparation of the Detailed Project Report (DPR) on Saptkosi High Dam on the Kosi.

Both sides reiterated their commitment to expediting the work on preparation of the DPR of Saptkosi High Dam project during the meeting which concluded on Wednesday in Kathmandu. Nepal assured full administrative support and security to Indian engineers.

After the breach, on August 18-19, 2008 Nepal government had said that Kosi treaty is a "historic blunder" but Nepal government's inconsistent and ambiguous position now on the Kosi High Dam proposal based on the same treaty must be exposed in the Nepali parliament and media.

In order to save Kosi region from an ecological and human disaster, Nepali and Indian legislators must take a categorical position based on a referendum on Kosi.

Gopal Krishna

Solution to floods: New paradigm needed

Md Khalequzzaman, The Daily Star, 2008-10-11

Bangladesh

Following the recent devastating floods in North Bihar, the Deputy Chairman of the Indian Planning Commission Montek Singh Ahluwali said in an interview, “the flood caused by the Kosi in Bihar underlies the need for storing water by building dams or barrages. Since the issue involves Nepal, vigorous diplomatic efforts are needed.” He also said that he did not see any other visible solution. It is a sorry state of affairs that the Planning Commission of India is still trapped within a failed paradigm of engineering and structural solution to a natural process, namely flooding. How long will it take for our policy makers to realize that flooding is a natural process, and it can't be "managed”?

We cannot defy the nature, we need to live in harmony with it. A recent fact finding report for the Kosi floods of 2008, prepared by a civil society organization under the leadership of Dr. Sudhir Sharma, Dr. Dinesh Mishra, and Gopal Krishna of India, highlighted that although India has built over 3000 km of embankments in Bihar over the last few decades, the flooding propensity has increased by 2.5 times during the same time period, not to mention that embankments failed during each major flooding event. Embankments provide a false sense of security to people living behind them. It has been proved time and again that no matter how strong the embankments are, and no matter who builds them (US, India, the Netherlands, China, Bangladesh, you just name it) they are destined to fail.

Every time there is a flood in Bihar or Assam, the people living downstream in Bangladesh get worried, since it take only a few days for flood waters in upstream regions to roll downstream in Bangladesh. However, the Kosi flood of 2008 revealed an interesting fact. Although parts of Bangladesh are located directly downstream of the Kosi confluence with the Ganges (called Padma in Bangladesh), no major floods occurred in those downstream areas following the deluge in North Bihar in mid August. Analyses of the data for river monitoring stations in the Padma at Pankha, which is located downstream of Farakka, showed that the stage of the river did not rise significantly following the floods in Bihar. The question that begs answer is why the flood in Bihar did not contribute to increased flow in the Padma in Bangladesh?

The answer lies in the underlying causes of flooding in Bihar. The breaching of embankment on the Kosi river allowed the flood waters to spread over the floodplains in North Bihar, resulting in reduced velocity and volume of flood waters that enter the Padma in Bangladesh. In addition, at the time of breaching, the flow of Kosi was only 1.4 lakh cusec, which is not an unusual flow during the monsoon period. The flood in Bihar was an unexpected phenomenon for the people living behind the embankments since they had a false sense of security. If the embankments were absent on either sides of the Kosi, the flow that caused a deluge in northern districts of Bihar probably would be an ordinary “two-day- flood” that would spread over wider floodplain areas in Nepal and Bihar, and would not cause any misery for select group of people who happened to be in the wrong place (downstream of where the embankments broke in Nepal) at the wrong time (August 18 and afterwards).

Despite an increase in investments for construction of embankments and other flood control measures, the intensity and magnitude of flooding have increased substantially in all co-riparian countries (Nepal, India and Bangladesh) within the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin in recent decades. All countries in the GBM basin are looking for solutions to flood damage to their economy and lives. However, so far there has been a minimum amount of involvement among co-riparian nations to tackle this common problem. All countries are working in isolation or in a bilateral manner to solve a problem that requires participation by all stakeholders living in the GBM basin. India, being the largest power and strategically located, needs to provide leadership role among the co-riparian nations (China, Nepal, Bhutan, India, and Bangladesh) and devise an integrated water resources management (IWRM) plan for the GBM basin.

The IWRM plan will require adaptation of a new paradigm that embraces an ecological approach to reducing flood damage through implementation of best management practices in land-uses in the entire basin (from the source to mouth of these mighty rivers). All people living in the floodplain of the GBM basin need to find a way to reduce land erosion and deforestation. Should they build on the floodplains, they need to adapt new construction standards that facilitate floodwaters flow under their houses, or be prepared to evacuate to higher grounds during high flow events. Drainage congestion due to urbanization and other land-use changes that increase surface run-off and reduce infiltration is another reason for increased flooding in the region. Widening of natural drainage network through dredging in proportion to the amount of urbanization, and increasing efficiency of storm sewage system in urban centers will be essential to avoid water-logging and flooding.

All stakeholders living in a watershed area, regardless of their political boundaries -- need to work together, there are no other alternatives. The planner and decision makers in the basin countries can hide their face in the sand hoping that flooding will not occur again, but such wishful thinking will not stop floods or reduce damage to economy and the environment. Humans will have to make room for rivers to spread during flooding, because floodplains have been an integral part of any natural rivers for millions of years; whereas human invasion to floodplains and interference with the natural flow have been a relatively new phenomenon. Every time humans decide to change natural forces to meet their needs, it becomes a duty for them to study the laws of nature and abide by them. Sooner we realize that humans cannot defy the nature, we can only live in harmony with it, better it will be for the humanity, because natural forces will always outweigh any human endeavour. Rivers flowing over to floodplains is one of such natural laws.

Md Khalequzzaman is a member of the Bangla-desh Environment Network (BEN)

Failure of dams as flood control structures has been demonstrated in Orissa, Gujarat, Maharasthra and Jharkhand.

Disaster management and relief centric narrative that has become the dominant factor came in for severe criticism.

A white paper was demanded, while sharing the Hindi version of the Fact Finding Report on Kosi “Kosi “Pralay”: Bhayaavah Aapada Abhi Baaki Hai” sought accountability of Kosi High Level Committee (KHLC) and provide a remedy for the drainage crisis in North Bihar as was promised by the UPA government's Common Minimum Programme. All the activities of KHLC should be put in suspension till the time their liability is fixed and Justice Rajesh Balia Judicial Commission of inquiry set up on September 9, 2008 is completed. The commission’s recommendations must not meet the fate of several dozens of committees and it must recommend criminal charges against acts of omission and commission.

It is noteworthy that Union Water Resources Department Secretary, in a letter to the Bihar Irrigation Secretary on September 24, 2008 has questioned the locus standi of the judicial commission. The letter read: “The Kosi agreement is a bilateral agreement between two sovereign states, India and Nepal, and Bihar is not a party to either 1954 or the 1966 agreement.”

Water and Power Consultation Services (WAPCOS), a central government’s public sector undertaking has provided technical inputs to the Bihar government on possible ways to plug the breach at Kusaha in Nepal.

Participants included victims of embankments who expressed their anguish at the Delhi, Kathmandu and Patna centric deliberations and decision making. They called for a movement against Kosi High Dam, embankments and changing the current course of Kosi.

Amid news reports that Kosi's course will be restored by December 15 and the breach would be plugged by March 31, 2009 citing Kosi Breach Closure Advisory Technical Committee chairman Nilendu Sanyal and Ganga Flood Control Commission chairman R C Jha on 14 October, 2008 to finalise modalities on plugging the breach, some participants were opposed to the repair of the breach in Kusaha. Government must hear the views of these people before undertaking repair works.

Meanwhile, central government has sanctioned Rs 40 crore for the project and Bihar Cabinet has sanctioned Rs 197 crore. Bihar Water Resources Minister Bijendra Yadav has said tenders for the breach closure have been invited and bidding will take place after October 21.

Kosi is an international river and all interventions must show utmost sensitivity that does not bring a bad name to our country. The onus is the central government to avoid a situation which makes our country a laughing stock for mismanagement of rivers.

It emerged from the discussions that a list of "what not to do in Kosi basin" must be prepared before relying on the suggestions of retired and tired officials like Nilendu Sanyal and his ilk. Post-retirement enlightenment of engineers has more to do with their own rehabilitation less to do with kosi victims welfare.

People of Kosi basin are victims of development and the arrogance of governmental knowledge that are used to scare common people into silence and submission by their declarations such as "I Know the facts".

From K L Rao, Kanwar Sen, K N Lal to Nilendu Sanyal all of them gave flood control solutions...people in Kosi basin are victims of their solution.

Dr Mishra explained why Kosi has been flowing at a level higher than its adjoining mainland. The reduced cross-section of the river due to embankments was expected to facilitate the dredging of its bed. Instead, the Kosi offloaded silt into the river and raised the level of its bed. That the Kosi is among one of the highest silt-laden rivers in the country makes matters worse. Had the river been free to meander, it would have deposited fertile silt, collected from the slopes of Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga, across the plains of north Bihar. But that was not to be, as most of the silt carried over the years lies trapped between river banks, reducing the stream flow on the one hand and making the embankments vulnerable to breach on the other.

He also revisited historical records and official documents arguing that floods caused by this river are not man-made, they are devil-made. Devils being the nexus between politician-engineer-contractors that feeds on the status quo.

Participants included Himanshu Thakkar, Sudhirendar Sharma, Gopal Krishna, Arvind Chaudhary, Kuber Nath Lal, K P Kesari, R K Singh, S K Sinha, Ram Chandra Khan, Shaibal Gupta, PP Ghosh, Rakesh Bhatt, Vijayji, Shivanand Bhai, C P Sinha, C Uday Bhaskar, V N Sharma, RK Sinha, A K Verma, N Sharma, B Singh, Chandrashekhar, T Prasad, Kavindra Pandey, Prem Kumar Verma, Raj Ballabh and several others.

Kosi is synonymous with the history, culture of not only Mithila but whole of the Indian sub-continent. One cannot think of the Indian sub-continent without thinking about Ramayana (Sita) and Mahabharata (Karna). Ramayana and Mahabharata cannot be even imagined in the absence of Mithila. The structural solutions have already distorted the landscape of the Kosi-Mithila region, Kosi High Dam would turn out to be a monument of foolishness for generations to come. Like the villains of embankment proposal, all the kosi high dam proponents must be identified and dealt with by something like a Kosi Sansad.

The proposal to raise a 269-meter-high dam in Sunakhambi Khola on the Sapta Kosi river, 5 km north of Barahachhetra temple in Sunsari district appeared to be an unsound proposition of people who are caught in a time warp. Proposed "Sapta Kosi Multi Purpose Project" claims to irrigate 68,450 hectares in Nepal and provide remedy for drought-prone areas measuring 1,520,000 hectares in India. It is claimed that alongwith irrigation and flood control, about 3,500 MW of electrical power would also be generated from water stored in the 269-meter-high reservoir.

According to a preliminary impact study, the proposed high dam will displace 75,000 people from about 79 Village Development Committees (VDCs) in nine districts of Nepal alone. About 111 settlements in the 79 VDCs, sprawling over the banks of the Sun Kosi, Tamor, and Arun rivers, will be totally submerged, while 47 settlements will face partial submergence, and 138 will become fractionally submerged.

Opinions available in public domain say, "If the dam is going to cause such upheaval, can the crops produced from the 68,450 hectares of irrigated land in Nepal compensate for this huge loss?" argued the bimonthly magazine, Pro Public/Good Governance, in its report. Estimated losses in the North Bihar are yet to be ascertained.

Elsewhere on the web Vinay Jha, Editor, Mithila Times argues that the kosi High Dam is actually a population-control plan by the government; a dam break in an earthquake prone zone will eradicate poverty in a vast region by eradicating the poor. Narural flow of rivers and natural habitats must not be tampered with, which we must maintain if we want life to exist on Earth. Instead of a gigantic dam, what we need is a gigantic network of very small scale water management schemes, including a vast network of small dams in Himalayas. But Indian officials can never think or manage such schemes.

Earlier, the meeting of the Indo-Nepal Joint Committee on Water Resources in Kathmandu on October 2, 2008 agreed to expedite work on preparation of the Detailed Project Report (DPR) on Saptkosi High Dam on the Kosi.

Both sides reiterated their commitment to expediting the work on preparation of the DPR of Saptkosi High Dam project during the meeting which concluded on Wednesday in Kathmandu. Nepal assured full administrative support and security to Indian engineers.

After the breach, on August 18-19, 2008 Nepal government had said that Kosi treaty is a "historic blunder" but Nepal government's inconsistent and ambiguous position now on the Kosi High Dam proposal based on the same treaty must be exposed in the Nepali parliament and media.

In order to save Kosi region from an ecological and human disaster, Nepali and Indian legislators must take a categorical position based on a referendum on Kosi.

Gopal Krishna

Solution to floods: New paradigm needed

Md Khalequzzaman, The Daily Star, 2008-10-11

Bangladesh

Following the recent devastating floods in North Bihar, the Deputy Chairman of the Indian Planning Commission Montek Singh Ahluwali said in an interview, “the flood caused by the Kosi in Bihar underlies the need for storing water by building dams or barrages. Since the issue involves Nepal, vigorous diplomatic efforts are needed.” He also said that he did not see any other visible solution. It is a sorry state of affairs that the Planning Commission of India is still trapped within a failed paradigm of engineering and structural solution to a natural process, namely flooding. How long will it take for our policy makers to realize that flooding is a natural process, and it can't be "managed”?

We cannot defy the nature, we need to live in harmony with it. A recent fact finding report for the Kosi floods of 2008, prepared by a civil society organization under the leadership of Dr. Sudhir Sharma, Dr. Dinesh Mishra, and Gopal Krishna of India, highlighted that although India has built over 3000 km of embankments in Bihar over the last few decades, the flooding propensity has increased by 2.5 times during the same time period, not to mention that embankments failed during each major flooding event. Embankments provide a false sense of security to people living behind them. It has been proved time and again that no matter how strong the embankments are, and no matter who builds them (US, India, the Netherlands, China, Bangladesh, you just name it) they are destined to fail.

Every time there is a flood in Bihar or Assam, the people living downstream in Bangladesh get worried, since it take only a few days for flood waters in upstream regions to roll downstream in Bangladesh. However, the Kosi flood of 2008 revealed an interesting fact. Although parts of Bangladesh are located directly downstream of the Kosi confluence with the Ganges (called Padma in Bangladesh), no major floods occurred in those downstream areas following the deluge in North Bihar in mid August. Analyses of the data for river monitoring stations in the Padma at Pankha, which is located downstream of Farakka, showed that the stage of the river did not rise significantly following the floods in Bihar. The question that begs answer is why the flood in Bihar did not contribute to increased flow in the Padma in Bangladesh?

The answer lies in the underlying causes of flooding in Bihar. The breaching of embankment on the Kosi river allowed the flood waters to spread over the floodplains in North Bihar, resulting in reduced velocity and volume of flood waters that enter the Padma in Bangladesh. In addition, at the time of breaching, the flow of Kosi was only 1.4 lakh cusec, which is not an unusual flow during the monsoon period. The flood in Bihar was an unexpected phenomenon for the people living behind the embankments since they had a false sense of security. If the embankments were absent on either sides of the Kosi, the flow that caused a deluge in northern districts of Bihar probably would be an ordinary “two-day- flood” that would spread over wider floodplain areas in Nepal and Bihar, and would not cause any misery for select group of people who happened to be in the wrong place (downstream of where the embankments broke in Nepal) at the wrong time (August 18 and afterwards).

Despite an increase in investments for construction of embankments and other flood control measures, the intensity and magnitude of flooding have increased substantially in all co-riparian countries (Nepal, India and Bangladesh) within the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin in recent decades. All countries in the GBM basin are looking for solutions to flood damage to their economy and lives. However, so far there has been a minimum amount of involvement among co-riparian nations to tackle this common problem. All countries are working in isolation or in a bilateral manner to solve a problem that requires participation by all stakeholders living in the GBM basin. India, being the largest power and strategically located, needs to provide leadership role among the co-riparian nations (China, Nepal, Bhutan, India, and Bangladesh) and devise an integrated water resources management (IWRM) plan for the GBM basin.

The IWRM plan will require adaptation of a new paradigm that embraces an ecological approach to reducing flood damage through implementation of best management practices in land-uses in the entire basin (from the source to mouth of these mighty rivers). All people living in the floodplain of the GBM basin need to find a way to reduce land erosion and deforestation. Should they build on the floodplains, they need to adapt new construction standards that facilitate floodwaters flow under their houses, or be prepared to evacuate to higher grounds during high flow events. Drainage congestion due to urbanization and other land-use changes that increase surface run-off and reduce infiltration is another reason for increased flooding in the region. Widening of natural drainage network through dredging in proportion to the amount of urbanization, and increasing efficiency of storm sewage system in urban centers will be essential to avoid water-logging and flooding.

All stakeholders living in a watershed area, regardless of their political boundaries -- need to work together, there are no other alternatives. The planner and decision makers in the basin countries can hide their face in the sand hoping that flooding will not occur again, but such wishful thinking will not stop floods or reduce damage to economy and the environment. Humans will have to make room for rivers to spread during flooding, because floodplains have been an integral part of any natural rivers for millions of years; whereas human invasion to floodplains and interference with the natural flow have been a relatively new phenomenon. Every time humans decide to change natural forces to meet their needs, it becomes a duty for them to study the laws of nature and abide by them. Sooner we realize that humans cannot defy the nature, we can only live in harmony with it, better it will be for the humanity, because natural forces will always outweigh any human endeavour. Rivers flowing over to floodplains is one of such natural laws.

Md Khalequzzaman is a member of the Bangla-desh Environment Network (BEN)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)