9 April 2010 - The Kosi river in north Bihar, which meandered through 15 different channels over 160 kms for 250 years, was finally ‘tamed’ in 1962-63. To arrest her strong currents, embankments were built on either side of its westernmost 8 to16 km-wide channel. However, this move also ended up entrapping 12 lakh population. Over the past 50 years, two generations of people living on this 160-km-wide stretch have forgotten how their forefathers lived with the floods, came up with a decent farm produce, and slept in peace trusting that Kosi would never bother them.

A bridge that collapsed and got buried under the silt at Birpur. It was one of the first casualties of the 2008 floods following the Kusaha breach. Pic: Surekha Sule.

Although the people have been witnessing adverse consequences of this ‘intervention’ ever since the embankments were built, the worst possible disaster struck them when a breach at Kusaha in Nepal on August 18, 2008, turned them into paupers overnight taking away their peace forever. The fertile soil they had so fondly tended to was transformed into wasteland with heavy sand silt. The victims entrapped within have been wailing over this predicament for five decades, in vain. Now those living outside the embankments have also joined the chorus. Whose benefit and security are these embankments for? Isn’t it a lose-lose situation?

The Kosi yatra

I was part of the 12-member media team that toured the Kosi basin along with the members of Barh Mukti Abhiyan and Kosi Adhyayan Dal recently. The ruined roads, caved-in bridges, collapsed houses, and sand-cast farms grimly reminded us of the horror left behind by the 2008 flash floods. We drove miles and miles through the white soft sand dotted with a few green patches and large water-logged areas covered with deadly hyacinth. Human habitation on either side of the rough-hewn road did not seem to end as people prefer staying closer to the roads for quick escape. Except for the embankments and a few elevations, there were no safe spots.

Even now, the people have nothing to work on. Distress migration to Delhi, Kolkata, Punjab, Haryana, etc., is rampant.

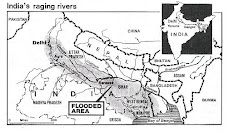

The Kosi yatra commenced at Khagaria – known as Saat Nadiyonka Sasuraal (Seven Rivers’ Marital Home) as all the seven rivers of north Bihar converge upon Khagaria (see map) which comes under the spell of floods each year without fail. With Saharsa as our base camp, the visits included three categories: the 2008 flood victims’ area in Supaul, the villages within the embankments, and the settlements (officially called ‘encroachments’) on the embankments.

Khagaria

Khagaria carries an unenviable epithet -- “Duba” (drowned) district -- as not a single inch of land has been left untouched by the rivers. It is being cordoned off in a 26-km-long, 12-15-foot-high ring-like embankment. The notoriety is such that demanding cars or motorcycles for dowry is passé; people now prefer boats as this is the mode of transport Khagaria relies on from June to October. In fact, they cite the example of an IAS officer who got a fibre boat in dowry. During floods, people shift to the upper stories, live on the roads or railway lines, and even embankments.

Village Manganj (east), block Triveniganj, district Supaul

On the fateful August 20, 2008, Reenadevi’s husband Ramesh Sah, a halwai, had gone to Triveniganj to cook a feast. When the floodwaters kept surging, Reenadevi shifted her children to a cot first and then to a table placed on top of it. Then again, she placed a few boxes on top of the table. Finally, she had to shift them to a nearby house perching on an elevation. They were rescued only after a week when Ramesh came in a rescue boat and took them to Triveniganj. The family came back in November only to find everything destroyed by the floods.

Some villagers said they somehow managed to live through the nightmare in five-seven feet of water for a few days by staying on rooftops. When some of them tried to escape, 16 persons were swept away by the strong currents. “Humne apni lungi utharke bahenko bachaya (I took off my lungi to save my sister),” said a villager. Although the area was water-logged for four months, it took two months for the relief teams to arrive.

The Manganj people had not experienced floods for over 50 years. The excess rainwater used to seep into large swathes of land and dry up on its own. They reaped the benefits through the enriched soil and put up with the inevitable periodic devastation. Now, having lost the fertile strips to white sand deposition left behind by months of water-logging, the families witness at least one member of the family migrating to Delhi or Punjab in search of work. No wonder a new phrase is doing the rounds: “dhotiwale Punjab/Haryana khet mein, pantwale Delhi mein”.

Village Ghiwaha, Block Chhatapur, District Supaul

At Ghiwaha too, as the ominous waters kept rising, the panic-stricken lot ran helter-skelter but had few safe spots to take refuge in. While some reached relief camps, others stayed with relatives or somehow made it to Nepal, Delhi, Kolkata, or Mumbai. For those left behind, it was a nightmare as the administration could reach them only after a week and distribute an emergency relief package containing one quintal rice/wheat and Rs 4,000 compensation. However, many needy families were left out.

The agony did not end here. Relief is yet to reach the families of five victims who died of snakebites. It’s been two years since the floods washed away the power lines and roads; but neither has been restored yet. Education and health services have come to a standstill and the area still remains cut off from the rest of the world.

When asked about the floods experienced 50 years ago, an elderly Ramprakash Mandal said the floods did not cause such widespread destruction then as the waters used to flow over a 40-km-wide stretch and recede soon. People were used to it and even prepared for it. But this time, they were caught unawares. The silt destroyed the land -- their only means of livelihood. “Then population was less. Farmers grew bajra and maize; not rice or wheat as is being done now.”

Ramprakash Mandal said how, with a lot of efforts, they sowed the seeds of an agricultural revolution through organic farming. The 2008 calamity wiped out everything with just one stroke and now they are back to 1962.

That calls into question the very rationale behind building the embankments. However, Shaligram Pandey still thinks embankments should be there but maintained well so that they do not breach again. Such high expectation from the administration despite the destruction caused by repeated breaches!

Mandal said: “Ek yug bita (an era has gone by). And people’s mindset has changed.”

From here, we reached Daheria village, block Chhatapur, district Supaul. The situation was no different here either. The same uprooted lives, destroyed infrastructure, and withered hopes.

Birpur and Bhimnagar barrage in Nepal

We witnessed tremendous devastation at Birpur bordering Nepal -- the first casualty of the 2008 floods on the Indian side following the Kusaha breach. The floods have wreaked havoc on many buildings and a highway bridge. The foundations of many houses have been washed away but some upper structures still stand precariously tilted to the sides. White sand deposits, water bodies and rivers filled with water hyacinth are a common sight. We also visited Bhimnagar barrage in Nepal later in the evening.

Village Sirwar within the embankment, district Supaul

Sirwar too has lost its roads and power lines to the floods and has been living in isolation. Boat rides through Kosi channels are the only means to reach the villages. The predicament of around 4000 population in this village is such that not a single government official or a teacher or a health worker visits them.

Mohammed Hasim, 70, remembers embankments being build around late 50s. He is one of the few lucky ones to have bought a nine-bigha land from a Rajput owner on a slight elevation. He cultivates wheat, maize in rabi season; not rice. He said: “When Kosi is in spate, we save our lives by climbing on the embankments. Then there is water all around. We get coupons but never get any relief material. Relief comes here but never reaches us. We do not know what administration means.”

In the absence of proper toilets, Ushadevi, Rajodevi, Shantidevi, and Reetadevi spoke about how difficult it gets, especially for women, when there is water all around for three-four months. People swim to neighbours’ houses as boats float only for fetching supplies, health emergencies, or to ferry people to the village from outside. During one such ordeal, Mohmed Niyamad’s niece drowned as she got stuck in a swamp and could not be saved. Snakes float in the water and many people have died of snakebites too.

There have been various tragic instances of people dying on the way to the health centre located outside the embankment. The village doesn’t have a trained midwife and deliveries take place at home. When the situation gets complicated, death seems to be imminent. In 2009, Ramdev Sharma’s daughter died on her way to the hospital to deliver her baby. Similarly, Momina Khatun’s 18-year-old daughter Rabbo’s baby and Basudev Sharma (40) who suffered stomach pain died even before reaching the hospital.

Matrimonial ties between the people living outside the embankments and those living inside are rare. Only poor families outside the embankments entertain matrimony as it costs them only one rupee. They call it mangani me shaadi (married at a cost required for engagement).

Three caste groups – Sharma, Yadav and Muslim -- live in Sirwar. Others are Bhagat, Thakur, etc. Most of them are “hasuva faros” -- one having no resource to work with. They have only a sickle to cut grass in other people’s fields. Everybody’s land has gone under water. Influential Rajputs from outside the embankments corner the land and give it out for tilling on the basis of sharecropping or rent or sale.

NREGA activist Suman Kumar Mishra said the works under the scheme have been undertaken using tractors and wages are deposited in the labourers’ bank accounts. When the latter withdraw money from the bank, contractors’ musclemen snatch the cash. Some 60 percent of daily-wagers have job cards but no money throughout the year.

At Khagaria, the Kosi river merges with the Kamla. Pic: Surekha Sule.

At Khagaria, the Kosi river merges with the Kamla. Pic: Surekha Sule. Momina Khatun, whose son Mehmood Moosa has migrated to Dehradun as a construction worker, said: “every woman’s husband is out for work and 10-15 men migrate for work each day.” On an average, Mehmood sends Rs 500-700 per month through someone coming home and informs her on someone’s mobile in the village. Momina’s husband died four years ago perhaps due to vocal cord cancer. Her second son lives with his family separately and her daughters are married. Her daughter-in-law works in the farm during harvest and gets one out of the 12 lots (boja) she cuts; i.e. some 50 kg of cereals over two months of rabi. They own two goats and a buffalo.

Saheb Sharma has three sons, three daughters (aged 2-14) and lives with his wife and old parents. He studied up to inter college in 1994, went to Delhi for work but landed up in menial jobs. He met with an accident while on duty and came back after two years. Now he works as a farm labourer and often takes land on rent. He has two cows, but milk does not fetch good returns here. On an average, Saheb Sharma earns Rs 1400-1500 per month, gets some cereals after farming, but pays half of the farm produce as rent to the landowner. His brother is in Dehardun and his wife with six children stays next door. Children go to school which have no teachers and hence, Saheb pays Rs 20 a month to a village youth for tuitions.

Entire population in Sirwar entrapped between the embankments lives below subsistence level and has no contact with the outside world except for a few mobile phones. The official response is as callous as it gets. They say the people have no business to live within the embankments as “they have been resettled”. Some 50 years ago, they were given land only for housing but not for farming. They were expected to till their land within the embankments after the flood waters receded. But the resettlements outside the embankments too have been water-logged and the people were forced to shift back to the villages or on the embankments. Their farmland within the embankments too went under water. There are some villages which got submerged several times in the last 50 years.

Village Belwara on the embankment, block Simri Bakhtiyarpur, district Saharsha

Despite such devastation, the official ‘solution’ to embankment breaches has been to raise the height of the dam from 8 to 15 feet. According to activist Dr Dinesh Mishra, “the raised embankments can be even more dangerous. The higher the embankments, the more the water held within which exerts far higher pressure on the walls. And if the embankment breaches, a lot more water will force out engulfing the nearby region for sure.”

We drove on the embankments in Simri Bakhtiyarpur block where soil was stocked on the embankment for construction. We had to cut short our journey as the jeep wheels got stuck in the soft white topsoil.

From the embankment, the difference in height between the riverbed level and outside the embankment was glaring. Because of the heavy silt accumulated over five decades, the Kosi riverbed here got raised by seven feet and hence the water flows at a higher level. On the way, we saw a collapsed sluice gate buried under the silt which was originally built to discharge water of a tributary into the Kosi. Since this tributary cannot discharge water into the main river, its water flows parallel to the Kosi outside the embankment, thus pulling a huge area under it. The water seeps through the embankments and a large area adjacent to the embankment remains waterlogged.

Now that the work of heightening the embankment is on, the people living on this embankment since 1987 have been served with notices labeling them encroachers. “Where can we go? We can’t stay within the embankment, can’t live on it, or get resettled at a lower level outside because of water-logging,” the villagers lamented.

Jawaharkumar Sharma said: “Our grandfather/great grandfather got 0.2 acre land in compensation and now we are 25 in the family. What do we get out of it?”

Umeshkumar, 24, who has migrated to Delhi earns Rs 2000-4000 and sends 1000-1500 to his family consisting of parents, wife, two children, and two brothers. His family pays Rs 5 to talk to him on someone’s mobile in case of emergency.

Village Tilathi right outside the embankment, block Simri-Bakhtiyarpur, district Saharsa

Shankar Yadav of Tilathi said the villagers had to bear severe losses as the land was acquired for three different purposes: for embankments, excavation, and for resettlement of the villagers inside. However, water-logging forced them back to the villages inside or on the embankment.

The waterlogged area is covered with hyacinth which prohibits the growth of farm crops. Wherever land is available, they grow rice, maize, moong, and vegetables. But only two months of rabi farming doesn’t fetch them enough. This time, 75% of the maize sown did not bear seeds and according to the officials, it was because of extreme cold conditions. Such adversities have been triggering migration. People come back here during February-April for rabi season and leave again for Punjab-Haryana to harvest wheat. Trains commute overloaded and overcrowded all the time.

Shankar said life was better before the embankments were built. “All the families in the village had land; but after the embankment, both sides are suffering losses, no one gains. In fact, kala azar (visceral leishmaniasis), malaria, and other water-borne diseases strike us regularly.”

When asked if they would migrate to a developed area with the family, the villagers said: “where do we go from our birthplace? We need schools, colleges, hospitals, roads, factories, and cottage industries close to our village.”

Village Chandrayan adjacent to the embankment, block Nauhatta, district Saharsa

In 1984, the embankment here breached and this was the first village to come under the fury of the flash floods. It breached early in the morning and within hours, the flash floods washed away countless human beings and cattle.

Ramnarayan Thakur said: “we were in difficulty even before the breach as the water used to seep through the embankments into our village. We have never slept peacefully even after the breach was plugged. Our woes continue to torment us. The roads and the bridges have not been restored. We have no electricity since 1984.”

Baidyanath Jha said the river flows within the embankments seven feet above the ground level. “Another breach, and we will all be swept away by the flash floods.”

However, an interesting suggestion came from Puneshwar Yadav who said a new embankment should be built from Kusaha (the 2008 breach point in Nepal) to Kursela (where the Kosi merges with the Ganga).

Media intervention

During our yatra, conversations with mediapersons laid bare crippling lack of intellectual debate on this issue. According to them, the media has not been able to generate opinion even though life has been uprooted several times. Between the ruling party and the Opposition in Bihar, there’s a clear consensus about building the embankments and raising their height. In the Assembly sessions, they discuss flood relief distribution but seldom the cause behind the disaster.

Thanks to government restrictions, a journalist added, media has limitations and is far from free. A senior journalist narrated how his seniors pressured him to suppress the truth. It talks about how old the embankments are and how badly they are being maintained but never turn it into a campaign. But some concerned mediapersons said they keep the debate rolling outside the press and said they would support any movement by the people or voluntary organizations to drive home the message.

Embankments for whom?

Every village within, outside, and on the embankments in the Kosi basin is replete with such sordid tales. The families are fed by their dear ones who migrate and are left to fend for themselves for four months in the flood waters.

Flood relief is yet another racket! ⊕

Surekha Sule

9 Apr 2010

Surekha Sule is a freelance journalist and environmentalist based in Mumbai, and a Media Fellow of the Ministry of Water Resources of the Government of India.

URL for this article:

http://www.indiatogether.org/2010/apr/env-kosibank.htm